Recently I was browsing the awesome age (which I encourage everyone to look at and use if you haven’t already), and noticed something that I had always mistakenly assumed wasn’t possible with the Go standard library.

Is it possible to have short and long options using just the

flagpackage?

Apparently it is possible!

To give a little more context, the short options are those that start

with a single dash (-) and consist of a single letter, e.g: for most

command line argument to set verbose mode you’d use: -v.

In contrast, the long options are those that start with double dash -- and

consist of a word e.g: to use the same example of verbose mode that would be

--verbose.

In order to find this out let’s first write small program that uses the flag

package and discover how the invocation of them change the output:

First let’s create a directory where to put the program and initialize the go.mod:

$ mkdir -p ~/go_experiments/using_flag

$ cd !$

$ go mod init github.com/chibby0ne/$(basename $(pwd))

This creates a directory using_flag inside a go_experiments

directory located in your home directory and initializes a go mod with the

organization/user name chibby0ne (my username) and repository name the same

as the directory name (using_flag). Of course you can use your Github

username, but since this is just for experimentation it doesn’t really matter

the organization/username or module name you choose.

- The

!$used in the second line is a shortcut to refer to the last argument of the last command. Pretty neat huh? You can check more about it in the man pages of bash looking into history expansion

Now copy the following code in and write it to a main.go file, and build it

with go build

package main

import (

"fmt"

"flag"

)

func main() {

var verbose bool

flag.BoolVar(&verbose, "verbose", false, "verbose output")

flag.Parse()

if verbose {

fmt.Println("verbose is on")

}

}

This program should write: verbose is on to stdout whenever the verbose flag

is set, otherwise it shouldn’t print anything.

Let’s see the output with only no flag:

$ ./using_flag

$

No output as expected.

Let’s see the output with only one dash (as usually done):

$ ./using_flag -verbose

verbose is on

$

Now let’s see the output with two dashes:

$ ./using_flag --verbose

verbose is on

$

As you can see the flag package allows this usage with double dash or long

option format but its usage is not “well documented” in the package

documentation.

Why is this the case?

Let’s dig into what happens when we set a BoolVar (which is the case for any

XVar where X is any type). All the source code shown corresponds to go version

go1.16.4 linux/amd64:

// BoolVar defines a bool flag with specified name, default value, and usage string.

// The argument p points to a bool variable in which to store the value of the flag.

func BoolVar(p *bool, name string, value bool, usage string) {

CommandLine.Var(newBoolValue(value, p), name, usage)

}

Let’s decompose the magic out of this one liner:

- What does

newBoolValuedo?

// -- bool Value

type boolValue bool

func newBoolValue(val bool, p *bool) *boolValue {

*p = val

return (*boolValue)(p)

}

newBoolValue is an unexported (private in other languages terminology)

function that creates a boolValue which is an type alias for bool. The pointer to

bool passed (p in BoolVar and in newBoolValue functions) is assigned to

the default value (value in BoolVar function and val in newBoolValue

function).

Then the pointer to bool is casted to a pointer to boolValue and

returned.

You might be wondering: Why create this internal boolValue for simply

storing the bool?

Because bool needs to be augmented with methods used by the flags package,

such as Get(), Set() and String(), these methods satisfy the interfaces

used through the package which are Getter and Value.

type Getter interface {

Value

Get() interface{}

}

type Value interface {

String() string

Set(string) error

}

According to documentation: Value is the interface to the dynamic value

stored in a flag. Getter is an interface that allows the contents of

Value to be retrieved.

You can read more of the Getter and the Value interface in the documentation, but for now let’s continue with our dive.

- What is

CommandLineand what does its methodVardo?

// CommandLine is the default set of command-line flags, parsed from os.Args.

// The top-level functions such as BoolVar, Arg, and so on are wrappers for the

// methods of CommandLine.

var CommandLine = NewFlagSet(os.Args[0], ExitOnError)

As it’s very well described in the godoc, CommandLine is the default flag

set of command line flags for the given executable, (The name used to invoke

the program is always given by os.Args[0])

And the Var method:

// Var defines a flag with the specified name and usage string. The type and

// value of the flag are represented by the first argument, of type Value, which

// typically holds a user-defined implementation of Value. For instance, the

// caller could create a flag that turns a comma-separated string into a slice

// of strings by giving the slice the methods of Value; in particular, Set would

// decompose the comma-separated string into the slice.

func (f *FlagSet) Var(value Value, name string, usage string) {

// Remember the default value as a string; it won't change.

flag := &Flag{name, usage, value, value.String()}

_, alreadythere := f.formal[name]

if alreadythere {

var msg string

if f.name == "" {

msg = fmt.Sprintf("flag redefined: %s", name)

} else {

msg = fmt.Sprintf("%s flag redefined: %s", f.name, name)

}

fmt.Fprintln(f.Output(), msg)

panic(msg) // Happens only if flags are declared with identical names

}

if f.formal == nil {

f.formal = make(map[string]*Flag)

}

f.formal[name] = flag

}

There’s a lot going on in there but let’s go step by step.

The godoc mentions that Var’s first argument usually holds a user-defined

implementation of Value and it could have a custom Set() method that

converts its arguments into a slice or some other type aggregate type. In our

case that’s not the case but since it’s part of this method documentation

which is shown in the godoc it’s good to be as general as possible.

Looking at the code we see that:

- A

Flagis created.

flag := &Flag{name, usage, value, value.String()}

And a Flag is:

// A Flag represents the state of a flag.

type Flag struct {

Name string // name as it appears on command line

Usage string // help message

Value Value // value as set

DefValue string // default value (as text); for usage message

}

It’s simply a struct that aggregates the name, usage, value and default value.

- A check is made on a unexported map (

f.formal) which is part of theFlagSet(in this case ofCommandLine).

_, alreadythere := f.formal[name]

The FlagSet structure has several unexported fields of which the Var

function uses name (a string) and formal (a map of type [string]*Flag)

As can be seen here:

// A FlagSet represents a set of defined flags. The zero value of a FlagSet

// has no name and has ContinueOnError error handling.

//

// Flag names must be unique within a FlagSet. An attempt to define a flag whose

// name is already in use will cause a panic.

type FlagSet struct {

// Usage is the function called when an error occurs while parsing flags.

// The field is a function (not a method) that may be changed to point to

// a custom error handler. What happens after Usage is called depends

// on the ErrorHandling setting; for the command line, this defaults

// to ExitOnError, which exits the program after calling Usage.

Usage func()

name string

parsed bool

actual map[string]*Flag

formal map[string]*Flag

args []string // arguments after flags

errorHandling ErrorHandling

output io.Writer // nil means stderr; use Output() accessor

}

The check is made as can be seen to see if the flag is redefined, returning a different error depending on whether the flagSet has an empty name or not.

if alreadythere {

var msg string

if f.name == "" {

msg = fmt.Sprintf("flag redefined: %s", name)

} else {

msg = fmt.Sprintf("%s flag redefined: %s", f.name, name)

}

fmt.Fprintln(f.Output(), msg)

panic(msg) // Happens only if flags are declared with identical names

}

- If the map is not yet created (nil) then a maps is created.

if f.formal == nil {

f.formal = make(map[string]*Flag)

}

- Add an entry in the map with the name of the flag as key and the pointer to the flag itself as value.

f.formal[name] = flag

Now the next piece of the puzzle comes in the next line of our program:

flag.Parse().

Diving deep again:

// Parse parses the command-line flags from os.Args[1:]. Must be called

// after all flags are defined and before flags are accessed by the program.

func Parse() {

// Ignore errors; CommandLine is set for ExitOnError.

CommandLine.Parse(os.Args[1:])

}

We can see that it calls the Parse method of the *FlagSet CommandLine

with all the arguments passed to the executable.

// Parse parses flag definitions from the argument list, which should not

// include the command name. Must be called after all flags in the FlagSet

// are defined and before flags are accessed by the program.

// The return value will be ErrHelp if -help or -h were set but not defined.

func (f *FlagSet) Parse(arguments []string) error {

f.parsed = true

f.args = arguments

for {

seen, err := f.parseOne()

if seen {

continue

}

if err == nil {

break

}

switch f.errorHandling {

case ContinueOnError:

return err

case ExitOnError:

if err == ErrHelp {

os.Exit(0)

}

os.Exit(2)

case PanicOnError:

panic(err)

}

}

return nil

}

We can summarize this function as parsing each flag until all flags are parsed and either errors/panics in case of an error or returns nil in case there wasn’t any.

More specifically the loop ends if err returned from f.parseOne() is

nil, and continues if the seen returned by f.parseOne() is true.

Do note, that even though arguments passed are being assigned to f.args, the

for loop doesn’t explicitly iterate over them, instead it an infinite loops,

and f.parseOne() handles parsing and shifting the arguments passed.

As we can see the real key to understating the Parse method is f.parseOne():

// parseOne parses one flag. It reports whether a flag was seen.

func (f *FlagSet) parseOne() (bool, error) {

if len(f.args) == 0 {

return false, nil

}

s := f.args[0]

if len(s) < 2 || s[0] != '-' {

return false, nil

}

numMinuses := 1

if s[1] == '-' {

numMinuses++

if len(s) == 2 { // "--" terminates the flags

f.args = f.args[1:]

return false, nil

}

}

name := s[numMinuses:]

if len(name) == 0 || name[0] == '-' || name[0] == '=' {

return false, f.failf("bad flag syntax: %s", s)

}

// it's a flag. does it have an argument?

f.args = f.args[1:]

hasValue := false

value := ""

for i := 1; i < len(name); i++ { // equals cannot be first

if name[i] == '=' {

value = name[i+1:]

hasValue = true

name = name[0:i]

break

}

}

m := f.formal

flag, alreadythere := m[name] // BUG

if !alreadythere {

if name == "help" || name == "h" { // special case for nice help message.

f.usage()

return false, ErrHelp

}

return false, f.failf("flag provided but not defined: -%s", name)

}

if fv, ok := flag.Value.(boolFlag); ok && fv.IsBoolFlag() { // special case: doesn't need an arg

if hasValue {

if err := fv.Set(value); err != nil {

return false, f.failf("invalid boolean value %q for -%s: %v", value, name, err)

}

} else {

if err := fv.Set("true"); err != nil {

return false, f.failf("invalid boolean flag %s: %v", name, err)

}

}

} else {

// It must have a value, which might be the next argument.

if !hasValue && len(f.args) > 0 {

// value is the next arg

hasValue = true

value, f.args = f.args[0], f.args[1:]

}

if !hasValue {

return false, f.failf("flag needs an argument: -%s", name)

}

if err := flag.Value.Set(value); err != nil {

return false, f.failf("invalid value %q for flag -%s: %v", value, name, err)

}

}

if f.actual == nil {

f.actual = make(map[string]*Flag)

}

f.actual[name] = flag

return true, nil

}

Whoa! That’s a lot to unpack. Fortunately we don’t need to analyze the whole function to get to the single and double dashes logic, but let’s take it piecemeal:

- Check if there are no arguments:

if len(f.args) == 0 {

return false, nil

}

So if there are no arguments it simply ends parsing.

- Getting the first command line argument (the actual option/flag name)

s := f.args[0]

Since f.args was all the command line arguments with whom the executable was

called (this is simply assigning to s the first command line argument).

Later we will see that the f.args slice gets updated in this function, so

that it we advance the command line arguments seen.

In our example program, this would make:

s := "-verbose"

- The actual explanation of why the short and long options work

if len(s) < 2 || s[0] != '-' {

return false, nil

}

numMinuses := 1

if s[1] == '-' {

numMinuses++

if len(s) == 2 { // "--" terminates the flags

f.args = f.args[1:]

return false, nil

}

}

name := s[numMinuses:]

To explain this part let’s continue with the flag in our example program s,

but let’s assume we have invoked it with 2 dashes:

s := "--verbose"

The first if returns if the length of s is 1 or not if the first rune

(character) is not a dash. None of these is our case.

Since we don’t enter the body of the if statement the first rune must be a

dash, or minus as it is called in the code, then the numMinuses is set to 1.

The second if checks whether the second character of the string is a dash -

and if it is it increments the numMinuses to 2. If it isn’t then the body of

the if is skipped.

Then checks if s consist of just that: two dashes (--), since the two dashes

is the flags terminator as we can see the function returns also false, and nil

as before.

After this the name := s[numMinuses:] slices the string so as to only trim

the dashes and leave only the name of the flag.

i.e: name := "verbose"

And this is the reason why the standard library flag package works for both

single or double dashes.

Now if you’ve made it this far and you’re also learning this was also news to you, then I’m afraid this wasn’t a big reveal and is actually expected.

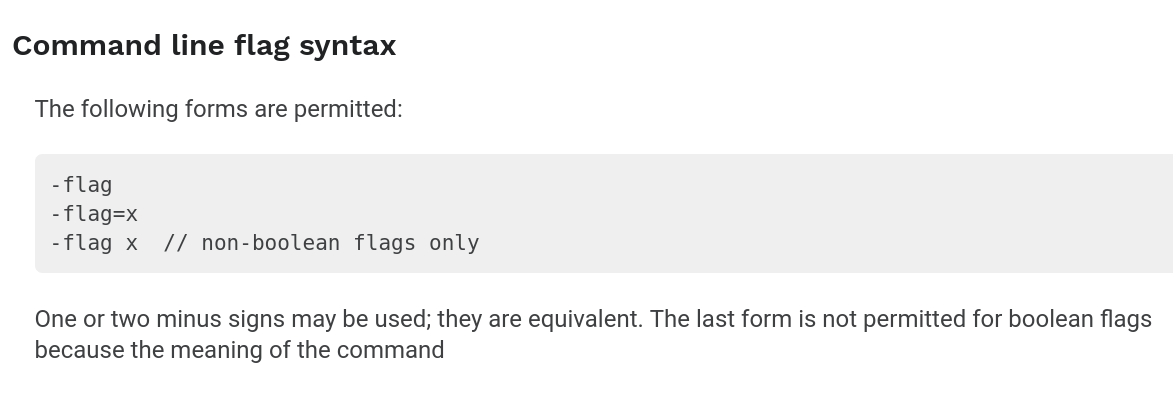

This is actually documented behavior, the thing is that is not actually well documented. From the docs, we can see that it shows 3 examples with a single dash but the text below mentions that double dashes are also possible.

So, yeah, RTFM am I right?

OK, great. But this still doesn’t answer the question: Is it possible to have short/long options using just flag package?

Well with this newfound knowledge of how flags are made and kept in the

*FlagSet this should be now a bit more straightforward, but let’s check how it

is done in

age

flag.BoolVar(&decryptFlag, "d", false, "decrypt the input")

flag.BoolVar(&decryptFlag, "decrypt", false, "decrypt the input")

flag.BoolVar(&encryptFlag, "e", false, "encrypt the input")

flag.BoolVar(&encryptFlag, "encrypt", false, "encrypt the input")

flag.BoolVar(&passFlag, "p", false, "use a passphrase")

flag.BoolVar(&passFlag, "passphrase", false, "use a passphrase")

As can be seen all that it’s needed is to assign to the same variable two

flags: one with a single letter and one with a word. Of course this doesn’t

prevent anyone from using the single dash with the word form or the double

dash with the single letter, but if the ergonomics and restricting the usages

are really important, you can always modify flag.Usage so that these two

cases are documented, as it is done with

age.

const usage = `Usage:

age [--encrypt] (-r RECIPIENT | -R PATH)... [--armor] [-o OUTPUT] [INPUT]

age [--encrypt] --passphrase [--armor] [-o OUTPUT] [INPUT]

age --decrypt [-i PATH]... [-o OUTPUT] [INPUT]

Options:

-e, --encrypt Encrypt the input to the output. Default if omitted.

-d, --decrypt Decrypt the input to the output.

-o, --output OUTPUT Write the result to the file at path OUTPUT.

-a, --armor Encrypt to a PEM encoded format.

-p, --passphrase Encrypt with a passphrase.

We can test it in our tiny example program by adding an extra line with "v"

as flag name such that it looks like this:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"flag"

)

func main() {

var verbose bool

flag.BoolVar(&verbose, "verbose", false, "verbose output")

flag.BoolVar(&verbose, "v", false, "verbose output")

flag.Parse()

if verbose {

fmt.Println("verbose is on")

}

}

Don’t forget to build it after modifying it.

Invoking it with -v, --v and of course the other two cases works as well:

$ ./using_flag -v

verbose is on

$ ./using_flag --verbose

verbose is on

$ ./using_flag --v

verbose is on

$ ./using_flag -verbose

verbose is on

And of course invoking it with three (or more dashes) dashes results in a error:

$ ./using_flag ---verbose

bad flag syntax: ---verbose

Usage of ./using_flag:

-v verbose output

-verbose

verbose output

$

For completion’s sake we’ll modify the flag.Usage so that we have a neater

error when we either print help or have an error parsing flags:

package main

import (

"flag"

"fmt"

)

const usage = `Usage of using_flag:

-v, --verbose verbose output

-h, --help prints help information

`

func main() {

var verbose bool

flag.BoolVar(&verbose, "verbose", false, "verbose output")

flag.BoolVar(&verbose, "v", false, "verbose output")

flag.Usage = func() { fmt.Print(usage) }

flag.Parse()

if verbose {

fmt.Println("verbose is on")

}

}

which outputs:

$ ./using_flag ---verbose

bad flag syntax: ---verbose

Usage of using_flag:

-v, --verbose verbose output

-h, --help prints help information

$

I think the main reason people assume this isn’t possible is because the flag documentation doesn’t show that the options could be passed with single or double dash. The fact that by far most people that want a CLI that handles flags cleaning use spf13/cobra doesn’t help either. Also it doesn’t help that is a high quality package with nice ergonomics.

But as you can see, it’s not essential to use in order to have regular Unix-style command line options.

That’s all folks. Happy hacking!

Last modified on 2021-05-14

You can make sure that the author wrote this post by copy-pasting this signature into this Keybase page.